Jam Roly-Poly

Or, How to Make a Grown Man Cry

No other pudding has lodged itself quite so deep in Britain’s heart as the jam roly-poly. It’s everything we were taught to love: the sturdy yet welcoming sponge, the appealing jam spiral, the absolute urgency to drown it in all custard. It’s the stuff of school canteens, where thick-armed dinner ladies dished out slabs of the still-steaming roll ready for us to sink our milk teeth into. It is decidedly not the stuff of restaurants, for the same reason birthday cake or chocolate pudding aren’t: it would feel like cheating. Jam roly-poly is built with the simplest of flavours - plain flour, butter, strawberry jam - and yet somehow, in this format, they taste better together than they have any right to.

In addition to being a miracle of simplicity, jam roly-poly is the perfect introduction to the two great oddities of British baking: suet and steaming. Suet is a hard fat found around animal kidneys that stays solid at room temperature. Thanks to this high melting point, it adds structure to puddings without turning greasy, and despite what the description may suggest, it tastes incredibly clean. Suet is as core to British baking as custard and silly names, and it’s there in all the greats: christmas pudding, mince pies, spotted dick, really anything called ‘pudding’.

Steam is what gives British baking an identity. It keeps sturdy doughs ultramoist through long cook times, and it produces hearty sponges with a bounciness that’s impossible to stop thinking about once you’ve tried it. In the days of unreliable or non-existent ovens, steaming was an ideal way to create a micro-environment of consistent temperature over any heat source. Since then, the advent of thermostat-controlled ovens in every kitchen has made steaming look fussy and impractical, and most of the western world has given up on it as a baking technique. But we are not in the business of practicality. We are in the business of joy. We are in the business of warm mouthfuls of sponge and sticky pools of melted syrup. We want to leave a pot on the stove and head out to the pub for the afternoon, confident that an extra hour here or there won’t matter a bit. Safe to say, once steaming is in your repertoire, you’ll forever have a foolproof and largely hands-off answer for any occasion that just needs something downright comforting and lovely. Luckily, jam roly-poly is the easiest version of steaming: it bakes inside a foil sleeve with a tray of water in the oven for good measure.

The challenge

When approaching jam roly-poly, I had two challenges. First, I knew I’d have to find a suitable alternative for suet, since it is nigh impossible to find in the US. Second, I wanted to see if I could push the texture even lighter and fluffier. As fabulous as it tastes, the roly poly does have a tendency to come out looking a bit flat and dense, which is fine for harried dinner ladies, but we can do better.

To replace the suet, I had three methods up my sleeve:

1) Grated brown butter, the brilliant idea of Camilla Wynne, who notes that browning the butter removes most of its water, thus raising its melting point, not to mention adding an outstanding nutty flavour

2) Shortening, typically sold as ‘Crisco’, America’s go-to ingredient for flaky pie crusts and the tenderest crumb cookies

3) Just more butter. This one defies all the logic of suet I just went to lengths to explain, but I have had success with it in christmas pudding and mincemeat, and I liked the idea of having one fewer ingredient on my list.

For added fluffiness, I turned to the closest roly-poly analogue I could find: the American biscuit. Like our suet sponge, biscuits are a tender short dough (as opposed to a long-chain glutinous, chewy sourdough), with rough chunks of fat distributed throughout. When they melt, these fat chunks leave air pockets in the dough which quickly puff up and separate the layers, giving us lightness and flake. To enhance all this airiness, biscuits typically use buttermilk or sour cream for added moisture, a pleasant tangy flavour, and for acidity, which aids in the rise by reacting with baking soda to create plentiful air bubbles. I had a plan.

The adventure begins

For a true suet-based yardstick, I turned to Paul Hollywood’s jam roly-poly recipe (minus the almonds and extract), and I almost cried. I hadn’t tasted that milky, warm, biscuity flavour since I stopped wearing pinafores, but there it was, so perfect and real I could almost feel my tights bunching up. My husband, a born-and-raised New Yorker with no prior exposure to the JRP said immediately, “It tastes like childhood.” I was so delighted with the results I almost stopped the experiment then and there. But the three pints of custard waiting in my fridge demanded more roly-poly, so I cracked on.

I was most intrigued about brown butter as a suet substitute, so I decided to start there. In this test, I also replaced a third of the milk with sour cream to get that promised biscuit lift. Browning the butter was a sensory delight in itself, but I started a bit too late and had an awkward two-hour waiting period for it to chill solid enough for me to attack with a box grater. Once truly firm and grated, this created a much softer dough than the suet, and it smelled unimaginably wonderful. What emerged, however, was a deep, honey-coloured sponge which was noticeably richer than the suet version, perhaps a tad too rich. The crumb was tender and moist, the acid, salt, and sugar were all in balance, but that was just the problem: this tasted like any and every good crumb cake, one I would happily serve in a modern bakery. But serve it down the pub, and no one would recognize it. I had been too clever for my own good, it seemed, and somewhere along the way lost the soul of the roly-poly.

Next was the shortening. Shortening is a miracle worker, but it’s also all the bad things: highly saturated, hydrogenated palm oil. Maybe for that reason I didn’t want it to work, but I have to say, in this fair test, it performed admirably, and was easy to use. Shortening is spoon soft at room temperature, but I had used up all my fridge patience on the brown butter, so I passed it through a potato ricer to break it up. In addition to some play-doh thrills, this worked well and the dough came together easily with a bit of extra flour to compensate for the softness. The result was completely decent. It had the essence of the roly-poly , and it was fluffier and more moist than the suet version, but everything about it just felt muted compared to my earlier mystical experience. Not bad, but not worth having to hand wash my ricer.

Finally, the butter. I used Clare Saffitz’s trick of grating a stick of frozen butter, which was both easy and satisfying, and the visible flecks of butter in the dough made me highly optimistic. This dough was more delicate than the suet version, but working quickly and keeping everything cold made it perfectly easy to handle, especially considering the whole thing comes together in about five minutes. The result was a complete surprise: a proud, puffed up roll, almost taller than it was wide. Even though I had long ago neglected the buttermilk/sour cream path, the butter alone delivered all that extra lift I had been seeking. And defying suet logic, the extra water in the butter had actually created more steam pockets, giving the dough a mighty upward thrust. While the flavour didn’t quite match the magic of that first suet bite, it was leaps and bounds closer than my other two attempts, and I was perfectly satisfied. More importantly, once drenched in custard, I could hardly tell the difference.

Jam Roly-Poly: The All-Butter Version

Serves 10-12. 15 mins active time, 1hr cooking time.

For custard, which is non-negotiable, I highly recommend this Serious Eats recipe (but skip the orange peel!)

For the jam roly-poly

250g / 1 3/4 cups all-purpose flour

40g / scant ¼ cup sugar

2 ½ tsp baking powder

4g / ½ tsp salt

Zest of ½ lemon

25g / 2 tbsp butter, chilled and cubed

100g / 7 tbsp butter, frozen and grated

150ml / ⅔ cup whole milk

1 tsp vanilla

120g of your favourite jam, ideally a nice dark colour for contrast. I like raspberry, but for the true school dinner experience, try strawberry. The stout of heart can even use golden syrup.

Before you do anything, freeze a stick of butter, ideally at least two hours before starting this recipe.

Preheat the oven to 400F/200C. Place a deep roasting pan on the lowest shelf and fill it with boiling water.

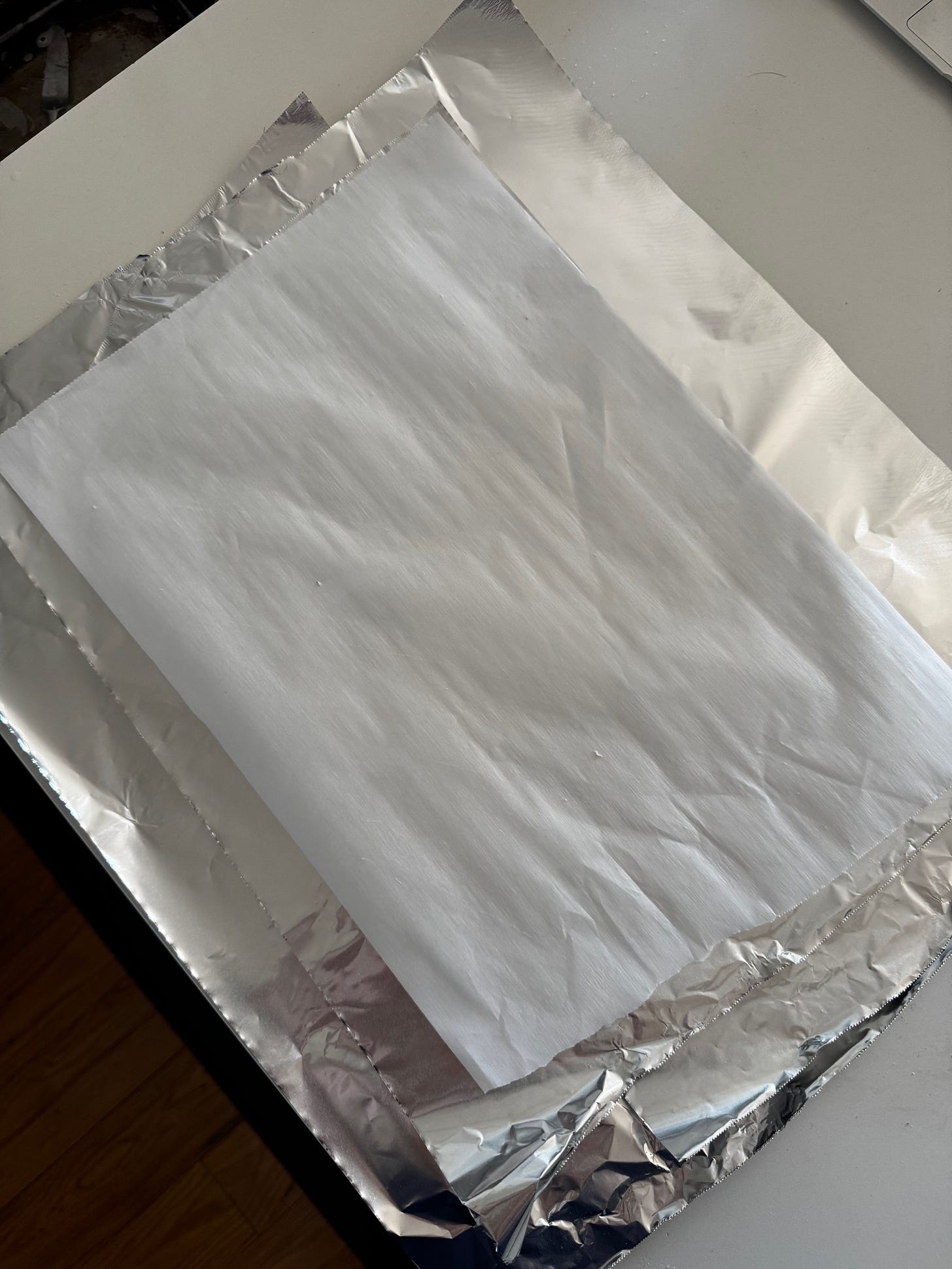

Prep your foil packet by laying out two 45cm/18” lengths of aluminium foil so they overlap. Lay another piece the same length in the middle to cover the seam. On top of these, lay a 35cm/14” length of parchment paper, greased with some butter. Set aside.

For the pastry, mix the 250g flour, 40g sugar, 2 ½ tsp baking powder, ½ tsp salt, and zest of ½ lemon together a large bowl. Add the 25g of chilled and cubed butter, and rub it into the dry ingredients until you have a fine sandy texture. This step coats the flour in fat to prevent it forming long, chewy gluten chains.

Grate the frozen stick of butter on the large holes of a box grater, until you have 100g, or 7 tbsp. An American stick of butter is 113 g / 8 tbsp, which leaves you a little melty hand hold at the end. If your hands are warm, hold the stick with a towel to keep it cool. Add the grated butter into the dry ingredients and mix to coat. Then add the 150ml milk and 1 tsp vanilla and mix to form a shaggy dough that holds together. It’s okay if there are a few dry patches at this stage

Tip the dough onto a clean surface and pat into a roughly 20cm x 30cm (7” x 12”) rectangle. Dust with extra flour as needed to stop the dough from sticking. Cut the dough in half along the long edge and stack the two halves. Pat it out again into a rectangle and repeat this stacking and patting two more times, working quickly so the butter doesn’t get too warm. This is a gentler way of bringing the dough together without kneading, or forming too much gluten.

Pat or roll the dough into a 20cm x 30cm (7” x 12”) rectangle and spread your jam almost to the edges, leaving a 1cm / 1.2” gap on one of the short sides. This will be your bottom seam. You might not need to use all the jam, as too much will cause it to splodge out during baking, but the layer should be thick enough that there are no dry bits of dough. Starting at the short end opposite your seam, gently lift the edge of the dough up, tuck it into itself, and start gently rolling it into a log. It the dough sticks to the counter, use a bench scraper or knife to gently coax it off. This is not a visual stunner of a dessert, so don’t stress about it, just try to avoid holes in the dough.

Gently move your roll onto the greased parchment paper. Lift up the long edges of the foil so they meet, and seal them together with a double seam, leaving plenty of room for the roly-poly to expand. Then seal the ends, making sure everything is airtight. Place your foil packet on a baking tray and into the oven on the middle rack.

If you haven’t already, this is a great time to make your custard!

Bake for 45 mins, then carefully peek inside the foil to check for doneness. It’s ready when the edges are browning, but the top is still pale, and it bounces back slightly when poked. If it’s not ready, give it an extra 10-15 minutes.

Remove from the oven and leave inside the sealed foil packet for 10 minutes, then remove and cut off the ends to reveal the jam swirl.

While the jam roly-poly tastes like heaven when served warm and fresh, it does dry out quite quickly once removed from its steam bath, so it’s best served as soon as possible and all at once (like, to two hundred rowdy schoolchildren), and with PLENTY of custard. If that’s not in the cards for you, the best way to reheat it is for 20s in the microwave.